Fatty liver disease is very common and can lead to serious health problems if ignored. Here is how to calculate your risk of having complications from a fatty liver, and how to find out if you would benefit from FibroScan testing.

What is fatty liver?

Fatty liver is a very common condition in the US, with an estimated prevalence of 40% of the population. Also known as hepatic steatosis, this condition is characterized by the presence of excess fat storage in the liver. If the liver holds on to enough excess fat, it can become enlarged, inflamed, and lead to more severe liver problem in the future. Recently, fatty liver was renamed to steatotic liver disease (SLD) to avoid the stigma associated with the word “fatty” but this change in nomenclature will take many years to catch on and most people will continue to refer to this condition as fatty liver disease for the foreseeable future.

What causes fatty liver?

Most cases of fatty liver are related to a condition called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) which was also recently renamed to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), but excess alcohol use is another common cause of fatty liver disease, as are many other liver conditions.

Who gets fatty liver?

Risk factors for developing fatty liver disease include diabetes, obesity, having other metabolic diseases such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or high triglycerides, or drinking excess alcohol (more than 2-3 drinks a day for men, or more than 1-2 drinks a day for women). Overall the metabolic dysfunction that leads to fatty liver is characterized by insulin resistance, low or dysfunctional muscle mass, and the inability to properly dispose of (meaning burn or store properly in liver or muscle) excess calories taken in from food sources.

Now let’s look at the main risk factors for fatty liver disease in more detail:

Diabetes: About 70% of patients with type 2 diabetes have fatty liver. Diabetics are the highest risk group of people to develop fatty liver.

Obesity: Living with obesity is a risk for fatty liver also. The easiest way to define obesity is to use the body mass index, or BMI, with a BMI greater than 30 defining obesity. Being overweight, meaning your BMI is between 25 and 30, is also a risk factor for fatty liver, especially if you have other metabolic risk factors.

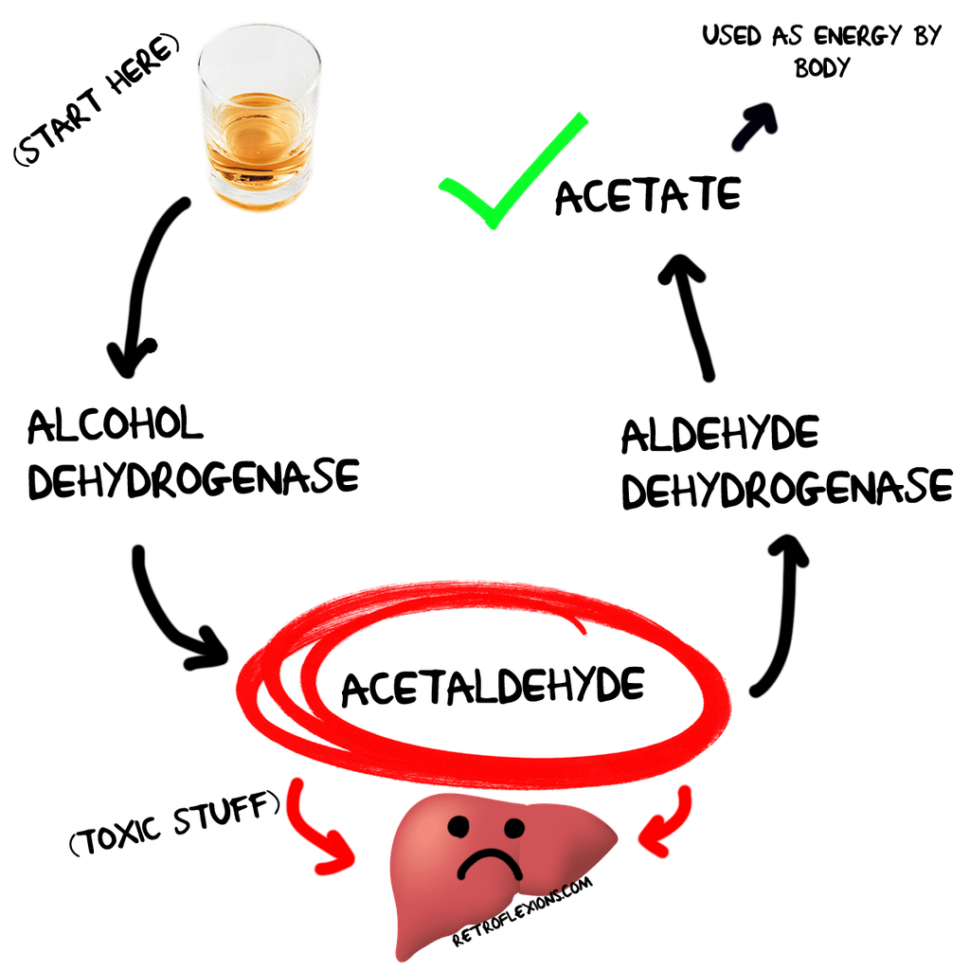

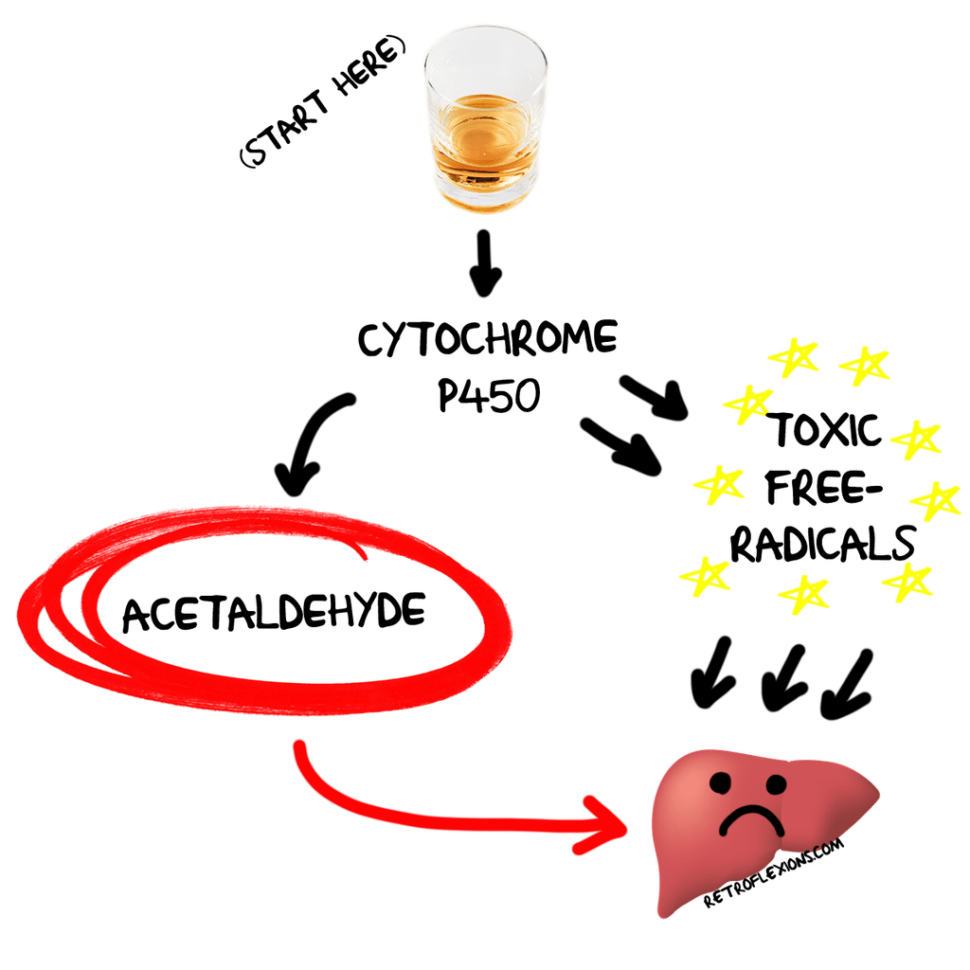

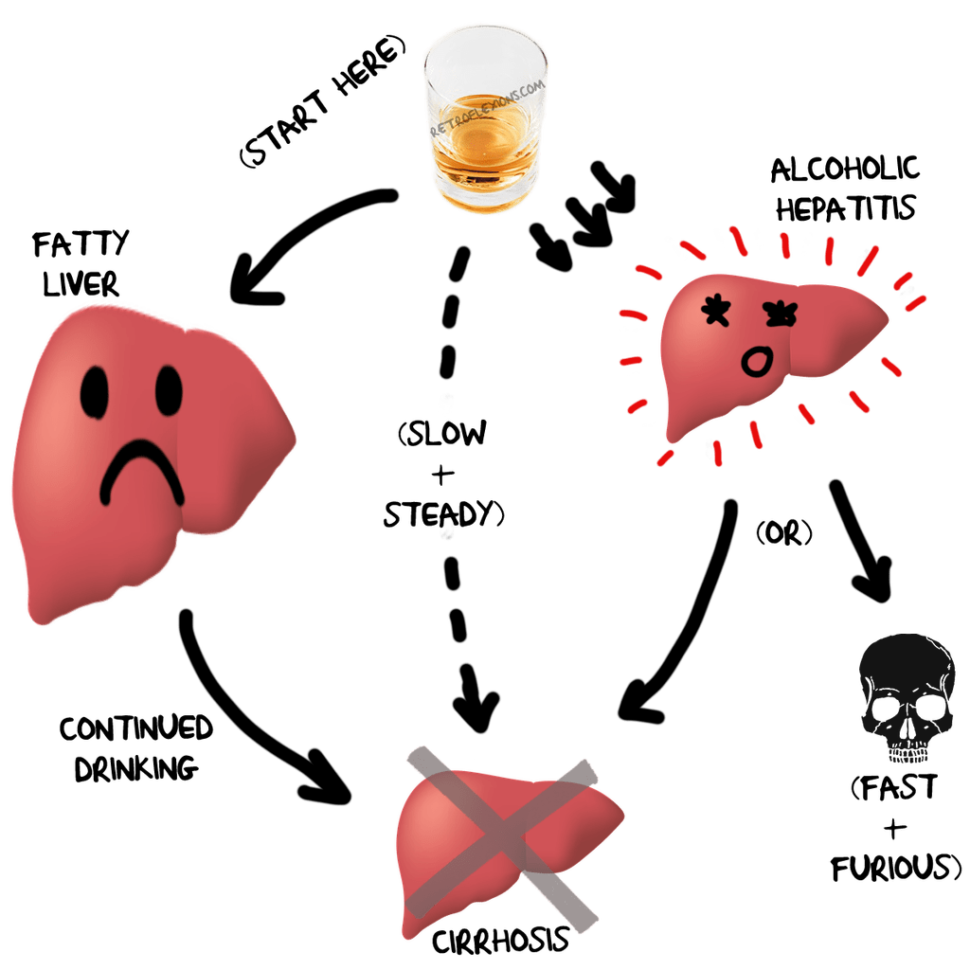

Alcohol: Alcohol use is a major cause of fatty liver disease, as well as alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis. The type of drink doesn’t matter, as a standard serving of beer (12 oz), wine (5 oz), and liquor (1.5 oz) all contain the same amount and type of alcohol. What really matters is the amount of alcohol consumed weekly, and the time (months to years) that this consumption goes on for. To illustrate this point with some real numbers, men < 65 years old are at risk of alcoholic liver disease by drinking more than 14 drinks per week, or more than 4 drinks per occasion, and women or people >65 years old are at risk by drinking more than 7 drinks per week, or more than 3 drinks per occasion. If these numbers seem low, that should drive home the point that alcohol is a toxin to the liver and should be significantly limited or better yet completely eliminated from the diet. Some people are more susceptible to the damaging effects of alcohol than others: In fact, cirrhosis can occur in up to 30% of people who consume only 2-3 drinks per day for many years.

Are there symptoms of fatty liver disease?

Often thought of as an asymptomatic condition, fatty liver disease actually does have several associated symptoms:

Abdominal pain: Typical pain from fatty liver is mild, dull, nagging and located in the right upper abdomen. Sometimes the pain is felt in the right flank and/or in the back too. The pain can be worse with bending forward, and is sometimes more noticeable in the evenings.

Fatigue: Since it’s an inflammatory condition, fatty liver can cause a feeling of generalized fatigue.

Pruritis: This is the fancy term for itchy skin. It’s typically mild or nonexistent in most people with fatty liver, but occasionally itchy skin becomes a problem with advanced fatty liver disease.

Metabolic dysfunction: While not technically a symptom, metabolic dysfunction is often the root cause behind the common complaints of the feeling of inability to lose weight, bloating, low energy, poor sleep, and so-called “brain fog” that often is associated with underlying insulin resistance and poor metabolic health. The onset of fatty liver is often one of the first measurable signs that something is very wrong.

Why is fatty liver dangerous?

By itself, having fatty liver alone increases your risk of several other non-liver related conditions, most notably heart disease, stroke, cancer, and also increases all-cause mortality (the risk of death in general). In non-diabetics, having fatty liver greatly increases the chance of developing diabetes in the future by contributing to a condition known as insulin resistance.

However, in some people with fatty liver disease, the liver cells become chronically inflamed. Blood tests may show elevated liver numbers (AST and ALT) because the damaged liver cells are leaking their enzymes into the blood. When liver inflammation from fatty liver occurs, it is called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, also known as NASH (this condition was also renamed recently to metabolic-dysfunction associated steatohepatitis, or MASH).

Left alone for a few years, people with inflamed fatty livers can slowly develop scar tissue in the liver called fibrosis. This scarring is the body’s attempt to repair the chronic inflammation from the inflamed liver cells. However unlike inflammation from a wound or surgery which typically gets better as time passes, the inflammation from NASH is ongoing, causing the body to lay down scar tissue in the liver for years and years. The end result of this process of progressive fibrosis of the liver is cirrhosis, or end-stage scarring in the liver that causes permanent dysfunction of the liver.

How do I know if I have fatty liver or liver fibrosis?

Despite the above symptoms, most people with fatty liver disease or liver fibrosis are walking around living their lives without a clue that there is liver damage happening behind the scenes.

Occasional blood testing to measure the liver enzymes is a decent way to evaluate for fatty liver disease. However, many patients with fatty liver disease and even patients with advanced liver damage may have completely normal liver function tests. An abdominal ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI can often suggest fatty liver too. However none of these methods are very accurate in identifying patients with advanced fatty liver disease, and liver biopsy remains the gold standard test for diagnosis of fatty liver, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis. However liver biopsy is invasive, sometimes painful, costly, and has significant risks like bleeding.

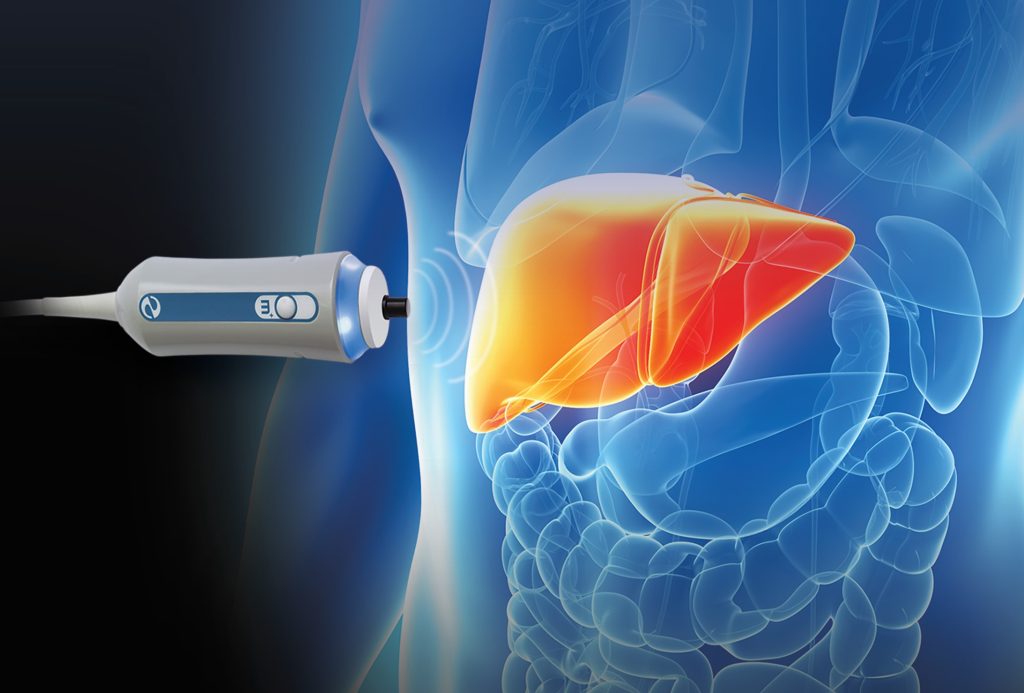

A more sophisticated test for fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis is called FibroScan. A FibroScan test is a type of ultrasound test that measures the physical properties of the liver to determine liver fat content and liver stiffness. FibroScan can be thought of as a non-invasive liver biopsy and it samples a larger area of liver tissue when compared with a traditional needle biopsy.

How does FibroScan work?

Fibroscan is painless, non-invasive, and takes about 5-10 minutes to perform. It is similar to a traditional ultrasound as it uses a small ultrasound probe to locate the liver, but instead of taking images of the liver, FibroScan is used to measure certain properties of the liver tissue instead.

FibroScan measures liver steatosis, meaning how much fat is contained in the liver. So instead of a traditional ultrasound or CT scan that just states (for example) mild fatty liver, or severe hepatic steatosis, FibroScan will produce a numerical value that corresponds to the amount of steatosis (fat) in the liver. This number is more accurate than just estimating the severity based on traditional imaging, and can be used to follow a patient’s progress as time goes on. When the steatosis number goes up, the fatty liver is becoming more severe. If the patient is successful in treating their fatty liver, we can watch the steatosis number improve which is proof that the disease is improving.

More importantly, FibroScan allows the measurement of liver fibrosis. This is the value that we truly care about, as fibrosis (liver scarring) is what ultimately correlates with all the bad outcomes of liver disease. If a patient is developing fibrosis, we need to take more drastic action to prevent the fibrosis from progressing into liver cirrhosis over the next few years. FibroScan measures fibrosis by calculating liver stiffness. To do this, the ultrasound probe will send a small pulsed vibration (it feels like a mild tap on the body) through the liver, and measure how fast the liver moves after this small vibration. The vibration wave will pass very quickly through a stiff liver, which means the liver tissue is fibrotic. The vibration wave will pass more slowly through healthy and pliable liver tissue, meaning no fibrosis is present.

Here is an analogy for how the FibroScan measures liver stiffness: Think of tapping your knuckle on a stiff surface like your kitchen table…the force travels rapidly across the table and if someone puts their ear to the other side of the table they would hear the tap almost instantly as it is transmitted through the table. Now try this same experiment on your couch cushion. This is a pliable (not stiff) surface, and the force of your tapping knuckles will be dissipated by the movement of the couch cushion and barely audible to a person with their ear on the couch. That’s how FibroScan works to measure liver stiffness and calculate liver fibrosis.

Who should get a FibroScan test?

There are several indications for FibroScan. Since fatty liver disease is severely underdiagnosed in the population (meaning many people are walking around with significant liver disease and don’t know about it), many of the major medical societies have recently changed their guidelines to push for early detection and treatment of fatty liver disease.

Before we get into the details, we need to review something called the FIB-4 score. This simple non-invasive scoring system was derived to help see who is at risk of more advanced liver disease (fibrosis). It requires only a few values available from routine blood tests: platelet count, AST, and ALT. You can calculate your FIB-4 score below.

- If your FIB-4 score is low (less than 1.3), you have a low risk of liver fibrosis.

- If your FIB-4 score is high (greater than or equal to 1.3), you are at higher risk of liver fibrosis and more testing is needed.

So who should check their FIB-4 score?

Patients who are obese: In patients with obesity (BMI>30), and the presence of two or more metabolic risk factors (high blood pressure, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, prediabetes), the FIB-4 score should be used to determine who needs further testing with FibroScan.

Patients with type 2 diabetes: All type 2 diabetics should be screened using the FIB-4 score, even without having other risk factors like obesity or metabolic syndrome.

If you are in one of the two groups above, and your FIB-4 score is greater than or equal to 1.3, you should get a FibroScan for further assessment of your liver.

Who else should get FibroScan testing?

Patients with elevated liver function tests (LFTs): If your liver tests are significantly elevated, you should have a complete evaluation to determine why this is the case. This typically involves further blood testing, ultrasound imaging, and often a FibroScan.

Patients with abnormal liver imaging: If you already have signs of fatty liver, fibrosis, or other signs of liver disease on imaging, you should consider FibroScan testing to better clarify your risk of developing more advanced liver disease.

Patients who consume a significant amount of alcohol: If you are worried about your drinking, or consume more than 21 drinks per week for a man, or 14 drinks per week for a woman, you should consider FibroScan testing to determine if you have fatty liver disease, fibrosis, or cirrhosis.

Conclusions

Fatty liver disease is very common and is a major risk factor for developing more severe liver diseases like fibrosis and cirrhosis. Most patients with diabetes, and many patients with obesity and other associated metabolic health problems have fatty liver disease. Alcohol is also a strong risk factor for developing liver disease. You can check the two most important measures of your liver health (steatosis and fibrosis) with a quick non-invasive FibroScan test.

Precision Digestive Care is the first practice in the Huntington area to offer FibroScan testing. This test is covered by most insurance plans. If you are in need of a FibroScan test, please contact us to schedule.