I’ll just start out by letting you know that I had mixed feelings about posting this. Not because I’m embarrassed to publicly discuss my colonoscopy experience (weirdly enough, I am OK with that part), but because I don’t want to be responsible for people interpreting what I’m about to disclose far too liberally and ruining their pre-colonoscopy cleanout. So please read on, but don’t push the limits too much. Failing to achieve a good bowel prep will require you to repeat the exam and prep again, and nobody wants that to happen!

For the past year or so I have been having minor IBS-type symptoms on and off, mostly related to stress or periods of poor diet. As a gastroenterologist, I started getting into my own head and worrying that I had some rare or catastrophic disease (the availability heuristic is real!) Part of me knew that if the test was normal, I would probably feel better just with that knowledge alone. I’d also be lying if I said that I wasn’t just a little curious about the whole process too. I either talk to people about colonoscopies or perform them for most of my waking hours; shouldn’t I also have some first-hand experience to reference for my patients?

So I scheduled a colonoscopy and requested Suprep bowel prep. I choose Suprep because it is what I usually give out to patients…I’ve noticed that most people seem to complain the least about the taste of Suprep when compared to most other preps. That’s not to say that the other preps are inferior…I use them interchangeably. However, I wasn’t about to get two or three more colonoscopies just to test out all the preps, so the Suprep experience is what you get to hear about!

I was given the usual instructions for split-dose bowel prep: 1) Clear liquids only the entire day prior to the procedure; 2) Take the first dose of prep at 5 PM and the second dose of prep 5 hours before the procedure start time; 3) Nothing to eat or drink after the second dose of prep. Pretty standard stuff, these are the instructions I usually give to my patients. Following this will lead to a good or excellent bowel prep in the vast majority of people. But what if I told you that I did something different but still achieved an excellent clean-out?

I was given the usual instructions for split-dose bowel prep: 1) Clear liquids only the entire day prior to the procedure; 2) Take the first dose of prep at 5 PM and the second dose of prep 5 hours before the procedure start time; 3) Nothing to eat or drink after the second dose of prep. Pretty standard stuff, these are the instructions I usually give to my patients. Following this will lead to a good or excellent bowel prep in the vast majority of people. But what if I told you that I did something different but still achieved an excellent clean-out?

I cheated on the prep. I ate solid food the day before. Now before anybody gets too excited, I ate a very limited and small amount of food, but it made a huge difference in the ability to tolerate the entire process. The following is my “justification” for my cheating, other than the obvious reason of “I was hungry.” I wake up around 5:00 AM or earlier every day. I usually wake up starving and if I don’t eat something within an hour or so of waking I usually feel weak and like my head is spinning. I’ve been this way as far as I can remember, even back in elementary school. I had a long day ahead of me at work, and knew that without some calories in me I would crash in the mid-morning while doing procedures and not be able to function well. “It’s for the patients,” is what I told myself. I almost believed it, too!

I cheated on the prep. I ate solid food the day before. Now before anybody gets too excited, I ate a very limited and small amount of food, but it made a huge difference in the ability to tolerate the entire process. The following is my “justification” for my cheating, other than the obvious reason of “I was hungry.” I wake up around 5:00 AM or earlier every day. I usually wake up starving and if I don’t eat something within an hour or so of waking I usually feel weak and like my head is spinning. I’ve been this way as far as I can remember, even back in elementary school. I had a long day ahead of me at work, and knew that without some calories in me I would crash in the mid-morning while doing procedures and not be able to function well. “It’s for the patients,” is what I told myself. I almost believed it, too!

So that morning I ate a good-sized bowl of plain vanilla yogurt (no toppings, nuts, fruit, etc.) I also had a few pieces of white toast with butter. We usually don’t have white bread in the house, but we were lucky to have an unseeded loaf of Italian bread from the night before that I toasted in the toaster and buttered up. For lunch, I had a huge gelato without any nuts or toppings. Throughout the day I drank black coffee and plenty of clear liquids.

I got home around 6PM that day (a little later that the recommended 5PM start time) and began drinking the prep. I mixed the first part of the prep with water as recommended and took a sip. Thinking that I’d be really slick, I used a straw to try and bypass my taste buds. “Not terrible,” I thought to myself, relieved that this process wasn’t going to be as bad as many patients made it sound. The prep tasted like a mixture of seawater, dish soap, and grape cough syrup…yum! A few sips later and I was rethinking this whole thing…the cumulative effect of drinking the prep made each sip taste grosser than the last. After drinking about one-quarter of the first 16 ounces of the stuff, I put the container in the fridge and took a 10-minute break to pace around the house and rethink my strategy.

I got home around 6PM that day (a little later that the recommended 5PM start time) and began drinking the prep. I mixed the first part of the prep with water as recommended and took a sip. Thinking that I’d be really slick, I used a straw to try and bypass my taste buds. “Not terrible,” I thought to myself, relieved that this process wasn’t going to be as bad as many patients made it sound. The prep tasted like a mixture of seawater, dish soap, and grape cough syrup…yum! A few sips later and I was rethinking this whole thing…the cumulative effect of drinking the prep made each sip taste grosser than the last. After drinking about one-quarter of the first 16 ounces of the stuff, I put the container in the fridge and took a 10-minute break to pace around the house and rethink my strategy.

Going back to the prep in the fridge, I took a few more sips through the straw. Why was it taking so long to drink this stuff? If this were water I could have drank the whole thing in five minutes. I think the straw is actually slowing the process down. I ditched the straw and was able to drink the prep much faster. A few gulps later I was half-way done with the first round. I put the container back in the fridge since the colder the prep was the less bad it tasted. It’s now about 6:20 PM and I suddenly felt a strange grumbling in my lower abdomen.

I was surprised at how fast this stuff works! I figured it would take an hour or so to have any effect, or at least give me some warning first. I was wrong on both counts! With 8 oz. of the nasty stuff down so-far, I was lucky that my bathroom was only a few steps away! Immediate watery diarrhea was the result. The thing I wasn’t expecting was the total lack of pain, cramps, or any discomfort whatsoever. It was as someone just opened the faucet, then closed it again. Magic!

I finished the rest of that evening’s prep over the following 20-30 minutes in between several other sprints to the bathroom. The prep was definitely easier to drink when cold straight out of the fridge. It was about 7PM and the bowel movements were coming fast and furious now. I also noticed that I was incredibly thirsty all of a sudden. I chugged 32 ounces of room temperature Gatorade in about five minutes flat. I wanted more, but only had tomorrow’s ration in the house. Therefore I drank a glass or two of water. By 9PM, all was quiet. I mixed tomorrow morning’s prep and put it in the fridge to chill overnight. I woke from sleep around 1AM for one more small bowel movement, but it was no big deal. I actually got decent sleep.

The next morning, I woke up at my usual time of 5AM. I drank 2 cups of black coffee as soon as I woke up. This was followed by another 16 oz. of Suprep over the next 45 minutes. I would gulp down about 4 oz. at a time, then rest for 10-15 minutes and repeat until done. This time, the bowel movements started immediately after taking the first bit of the prep and were mainly yellowish water. Another 32 oz. of Gatorade down the hatch and the process was complete. The last 2-3 bowel movements were literally clear water, like as clear as the water that comes out of the faucet. Cool, I did it!

Now would be a good time to talk about a study from a few years back. Thinking that improving the tolerance of the prep would remove one of the classic barriers for some people to do colonoscopy as well as decrease the number of broken appointments and inadequate preps, researchers randomized patients into two groups: One group received a clear liquid diet the entire day prior, and the other was able to eat a light breakfast and lunch with several food restrictions the day prior. Both groups then completed the standard bowel prep. The study showed exactly what we would expect: The people who starved all day were miserable, the people who ate a little were less miserable, and the quality of the bowel preps achieved were the same between the groups! The most interesting finding was that the group of patients who were restricted to only having clear liquids cancelled their appointments more than twice as frequently as the patients that were allowed to eat just a little. Hunger is a powerful force to compete with!

Now before you eat a bacon cheeseburger with fries, corn on the cob, and a salad the day before your colonoscopy, it’s very important to understand that these subjects (and yours truly) ate a very limited diet the day before the colonoscopy. Fibrous foods such as any fruits or vegetables are not allowed. Seeds, nuts, whole grains, fresh or dried herbs/seasonings, popcorn, and the like are definitely not allowed. Corn is probably the worst thing one can eat the day before having a colonoscopy!

What kind of foods are OK to eat the day before the colonoscopy? Low residue foods (low roughage) are ideal; these are processed flours (white bread, etc.), white rice, pasta, yogurt, gelato, and related snacks, eggs, lean meats, and other foods. A light breakfast is fine. A light snack around lunch time is OK too, but after that it’s clear liquids only. That means “dinner” is clears only: You don’t want food and bowel prep in your stomach at the same time, trust me.

What kind of foods are OK to eat the day before the colonoscopy? Low residue foods (low roughage) are ideal; these are processed flours (white bread, etc.), white rice, pasta, yogurt, gelato, and related snacks, eggs, lean meats, and other foods. A light breakfast is fine. A light snack around lunch time is OK too, but after that it’s clear liquids only. That means “dinner” is clears only: You don’t want food and bowel prep in your stomach at the same time, trust me.

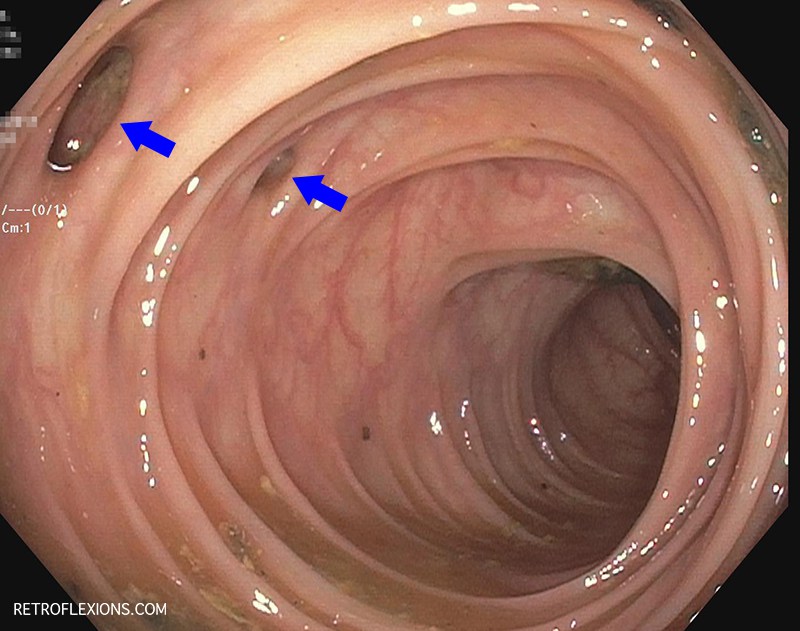

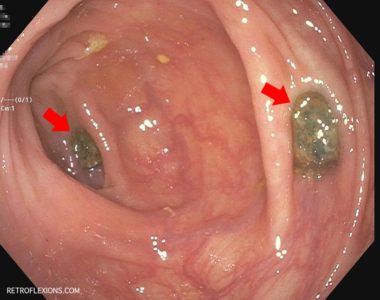

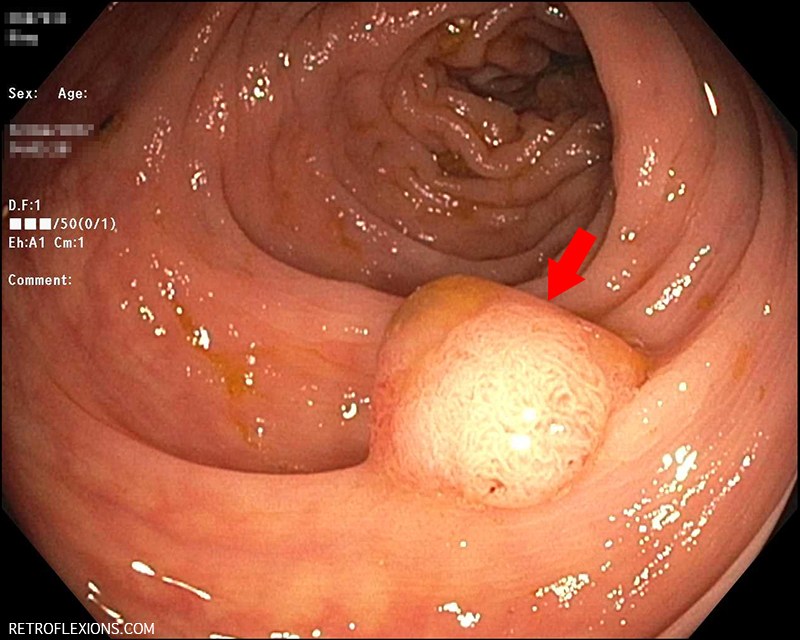

So back to the title of this article: A gastroenterologist cheats on the colonoscopy prep and wins! Did I really cheat? I guess not, since it seems that research backs up what I did! But did I win? Can you ever call getting a colonoscopy “winning?” I guess it depends on the findings. I did, however, have an excellent bowel prep!

I was given the usual instructions for split-dose bowel prep: 1) Clear liquids only the entire day prior to the procedure; 2) Take the first dose of prep at 5 PM and the second dose of prep 5 hours before the procedure start time; 3) Nothing to eat or drink after the second dose of prep. Pretty standard stuff, these are the instructions I usually give to my patients. Following this will lead to a good or excellent bowel prep in the vast majority of people. But what if I told you that I did something different but still achieved an excellent clean-out?

I was given the usual instructions for split-dose bowel prep: 1) Clear liquids only the entire day prior to the procedure; 2) Take the first dose of prep at 5 PM and the second dose of prep 5 hours before the procedure start time; 3) Nothing to eat or drink after the second dose of prep. Pretty standard stuff, these are the instructions I usually give to my patients. Following this will lead to a good or excellent bowel prep in the vast majority of people. But what if I told you that I did something different but still achieved an excellent clean-out? I cheated on the prep. I ate solid food the day before. Now before anybody gets too excited, I ate a very limited and small amount of food, but it made a huge difference in the ability to tolerate the entire process. The following is my “justification” for my cheating, other than the obvious reason of “I was hungry.” I wake up around 5:00 AM or earlier every day. I usually wake up starving and if I don’t eat something within an hour or so of waking I usually feel weak and like my head is spinning. I’ve been this way as far as I can remember, even back in elementary school. I had a long day ahead of me at work, and knew that without some calories in me I would crash in the mid-morning while doing procedures and not be able to function well. “It’s for the patients,” is what I told myself. I almost believed it, too!

I cheated on the prep. I ate solid food the day before. Now before anybody gets too excited, I ate a very limited and small amount of food, but it made a huge difference in the ability to tolerate the entire process. The following is my “justification” for my cheating, other than the obvious reason of “I was hungry.” I wake up around 5:00 AM or earlier every day. I usually wake up starving and if I don’t eat something within an hour or so of waking I usually feel weak and like my head is spinning. I’ve been this way as far as I can remember, even back in elementary school. I had a long day ahead of me at work, and knew that without some calories in me I would crash in the mid-morning while doing procedures and not be able to function well. “It’s for the patients,” is what I told myself. I almost believed it, too! I got home around 6PM that day (a little later that the recommended 5PM start time) and began drinking the prep. I mixed the first part of the prep with water as recommended and took a sip. Thinking that I’d be really slick, I used a straw to try and bypass my taste buds. “Not terrible,” I thought to myself, relieved that this process wasn’t going to be as bad as many patients made it sound. The prep tasted like a mixture of seawater, dish soap, and grape cough syrup…yum! A few sips later and I was rethinking this whole thing…the cumulative effect of drinking the prep made each sip taste grosser than the last. After drinking about one-quarter of the first 16 ounces of the stuff, I put the container in the fridge and took a 10-minute break to pace around the house and rethink my strategy.

I got home around 6PM that day (a little later that the recommended 5PM start time) and began drinking the prep. I mixed the first part of the prep with water as recommended and took a sip. Thinking that I’d be really slick, I used a straw to try and bypass my taste buds. “Not terrible,” I thought to myself, relieved that this process wasn’t going to be as bad as many patients made it sound. The prep tasted like a mixture of seawater, dish soap, and grape cough syrup…yum! A few sips later and I was rethinking this whole thing…the cumulative effect of drinking the prep made each sip taste grosser than the last. After drinking about one-quarter of the first 16 ounces of the stuff, I put the container in the fridge and took a 10-minute break to pace around the house and rethink my strategy. What kind of foods are OK to eat the day before the colonoscopy? Low residue foods (low roughage) are ideal; these are processed flours (white bread, etc.), white rice, pasta, yogurt, gelato, and related snacks, eggs, lean meats, and other foods. A light breakfast is fine. A light snack around lunch time is OK too, but after that it’s clear liquids only. That means “dinner” is clears only: You don’t want food and bowel prep in your stomach at the same time, trust me.

What kind of foods are OK to eat the day before the colonoscopy? Low residue foods (low roughage) are ideal; these are processed flours (white bread, etc.), white rice, pasta, yogurt, gelato, and related snacks, eggs, lean meats, and other foods. A light breakfast is fine. A light snack around lunch time is OK too, but after that it’s clear liquids only. That means “dinner” is clears only: You don’t want food and bowel prep in your stomach at the same time, trust me.

More specifically, ultra-processed foods are defined in this study as mass-produced packaged breads, snacks, confectionary, desserts, sodas and sweetened drinks; meat products such as chicken nuggets, meat balls, fish sticks and the like; instant noodles/soups, frozen ready-to-eat meals, and other food products made mostly of sugar, hydrogenated oils, fats, modified starches, and protein isolates. Often processed foods are deeply chemically processed and have flavoring agents, artificial coloring, and emulsifiers added.

More specifically, ultra-processed foods are defined in this study as mass-produced packaged breads, snacks, confectionary, desserts, sodas and sweetened drinks; meat products such as chicken nuggets, meat balls, fish sticks and the like; instant noodles/soups, frozen ready-to-eat meals, and other food products made mostly of sugar, hydrogenated oils, fats, modified starches, and protein isolates. Often processed foods are deeply chemically processed and have flavoring agents, artificial coloring, and emulsifiers added. Now that we have defined the problem, let’s take a second to realize just how much of this stuff most of us eat on a daily basis. How many of these “treats” do we open for ourselves or our children? Look in your pantry or freezer today and I bet there are a bunch of packages of snacks, cakes, muffins, frozen meatballs, chicken nuggets, and desserts in there looking right back at you. How many “foods” do we eat that were shaped by a machine into some pleasing shape and injected with modified fats and preservatives before being deep-fried, flash frozen and shipped out from a factory somewhere?

Now that we have defined the problem, let’s take a second to realize just how much of this stuff most of us eat on a daily basis. How many of these “treats” do we open for ourselves or our children? Look in your pantry or freezer today and I bet there are a bunch of packages of snacks, cakes, muffins, frozen meatballs, chicken nuggets, and desserts in there looking right back at you. How many “foods” do we eat that were shaped by a machine into some pleasing shape and injected with modified fats and preservatives before being deep-fried, flash frozen and shipped out from a factory somewhere?

So what is the bottom line? If we want to take care of our bodies the best we can, we should avoid these ultra-processed foods as much as possible. They are associated not only with high cholesterol, obesity, and high blood pressure, but now also with many different cancers. We should view these “foods” of convenience as what they really are, a shortcut to bad health at the sake of saving a little time. Eating junk food treats our taste buds to a temporary high at the cost of our long-term health. Knowing this, you can still enjoy the occasional doughnut or packaged snack, but this really should be a rare indulgence, not a daily or weekly occurrence.

So what is the bottom line? If we want to take care of our bodies the best we can, we should avoid these ultra-processed foods as much as possible. They are associated not only with high cholesterol, obesity, and high blood pressure, but now also with many different cancers. We should view these “foods” of convenience as what they really are, a shortcut to bad health at the sake of saving a little time. Eating junk food treats our taste buds to a temporary high at the cost of our long-term health. Knowing this, you can still enjoy the occasional doughnut or packaged snack, but this really should be a rare indulgence, not a daily or weekly occurrence.